Let me begin by expressing my gratitude to Deacon Brian for the invitation to be with you tonight, and for the warm hospitality offered by Most Holy Redeemer. I’m grateful for the bonds of affection that unite us in a common faith and witness, and long for the day when full visible communion between our two traditions, Roman and Anglican, is accomplished. Mindful of the recent visit between Pope Benedict and Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, I’m hopeful that our mutual love for one another here in

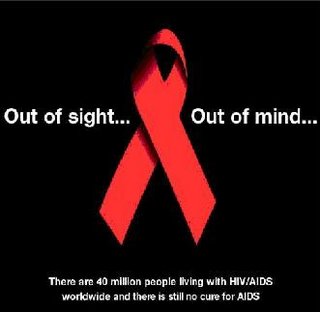

Let me begin by expressing my gratitude to Deacon Brian for the invitation to be with you tonight, and for the warm hospitality offered by Most Holy Redeemer. I’m grateful for the bonds of affection that unite us in a common faith and witness, and long for the day when full visible communion between our two traditions, Roman and Anglican, is accomplished. Mindful of the recent visit between Pope Benedict and Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, I’m hopeful that our mutual love for one another here in Tonight we gather to observe World AIDS Day. We gather to remember, to mourn, to celebrate, and to advocate. We come to this place for healing, and for the strength to continue to be agents of healing and reconciliation in a broken world. It is in light of this that I invite you to consider with me the extraordinary Gospel lesson we just heard, the story of the healing of the Centurion’s boyfriend.[i]

That this is the case here is underscored by the contrast between the use of pais to refer to the object the Centurion’s special concern, and the use of doulos, the Greek word for slave used to designate those under the Centurion’s command, the people he bosses around. Just any old slave would have been unlikely to garner the Centurion’s attention. He was moved to approach Jesus because of his love for his boyfriend.

If this seems like a strained reading of the story, consider that Matthew’s Gospel regularly makes subversive use of Gentiles, who bear all the marks of stereotypical paganism, contrasting their faith with the faithlessness of the religious authorities. The magi who pay homage to Jesus at his birth are pagan sorcerers of whom the rabbis taught: “He who learns from a magus is worthy of death.” Matthew’s bold claim that these foreigners recognized the Messiah, whom the religious leaders rejected, is remarkable.

Remember too the Syrophoenecian woman in Matthew 15, a worshipper of Baal whom Jesus refers to as a kunariois, a dog, which is slang for a temple prostitute. A woman, a gentile, and a prostitute: she was way beyond the pale of acceptance according to the law. And yet, her daughter is healed because of her audacious faith, pressing Jesus to transcend his own limited sense of mission to include this outsider.

And so it should not surprise us that Matthew’s Gospel, which plays brilliantly on the Hellenistic Jewish trope of Gentiles as sorcerers, idolaters, and sexual deviants, depicts a Roman soldier with a male lover as the exemplar of faith. It is this man who entrusts himself and his lover to Jesus in utter humility, without reservation, who is held up as our role model.

Jesus says of the Centurion, “Truly I tell you, in no one in

Jesus is telling us is that God does not divide up the world between insiders and outsiders the way we do. In fact, God turns things upside down, such that the outsiders are frequently those most open to the presence and power of God, while the pious are stone cold deaf to the Word of God that liberates and heals without distinction. Thus Jesus declares to the Pharisees, then and now, “the tax collectors and the prostitutes are going into the

It is not our moral superiority that heals us, but rather our trust in the mercy of God. In the age of AIDS, who knows that better than the countless men who have cradled their sick boyfriends, grieved their dead husbands, or entrusted themselves to the Christ who cares for them in the form of their beloved. Think of the men and women from our parishes who for 25 years or more have been such faithful agents of Christ’s healing: it takes my breath away. I think of Jane, who, after her son Steven died of AIDS, went on to help literally hundreds of other young men die with dignity. I think of the men who buried their lovers and then immediately opened their homes to care for their dying friends. I think of people, like my friend Cary, who had made his peace with God and was on his death bed, only to be resurrected by the development of anti-retroviral drugs. Now, he races in the AIDS Ride each year and is preparing to become a deacon in the Episcopal Church.

Then there is Bishop Gene Robinson, who was among the first people to go to

On this World AIDS Day, let us honor the truth that the tragedy of AIDS, despite its devastating impact, has given rise to powerful expressions of compassion and healing, and that it is men and women on the margins – like the Centurion and his boyfriend – who frequently have demonstrated the most faithful response to this ongoing pandemic. In the midst of so much death, the power of love has shone with an astonishing brightness.

Fenton Johnson, writing of his lover, Larry’s, death from AIDS, reminds us that “Grief is love’s alter ego, after all, yin to its yang, the necessary other; like night, grief has its own dark beauty. How may we know light without knowledge of dark? How may we know love without sorrow? ‘The disorientation following such loss can be terrible, I know,’ Wendell Berry wrote me on learning of Larry’s death. ‘But grief gives the full measure of love, and it is somehow reassuring to learn, even by suffering, how large and powerful love is.”[ii]

Shortly after Larry’s death, Fenton found himself driving to Muir Woods with his mother, reflecting on their memories of Larry, of love, and of loss. And then, his mother, rural

“I always thought of myself as tolerant and open-minded. I grew up with people who were gay, though of course back then we didn’t use that word. I knew some people in our town were gay, everyone knew they were gay, but I didn’t think much about that one way or another. Just live and let live, that’s my way of being in the world. And then you told me you were gay, and I guess I’d suspected it all along, and I just prayed that you’d stay healthy and find yourself a place where you could be happy. I prayed for all that and I was glad to see you get yourself to

Our challenge, today and everyday until there is a cure, is to demonstrate how large and powerful love is in the midst of AIDS. Like the Centurion, our love for our boyfriends, our daughters, our neighbors, our sons, our wives, for the whole human family created in God’s image, must be deepened by a humble trust that God loves us, has commissioned us to be agents of Christ’s healing, and has given us everything we need to do this work.

Let it not be said of us, “Truly, I tell you, in no one in the Church have I found such faith.” No, let us make our mantra these words of Jesus: “Go, let it be done for you according to your faith.” Amen.

[i] My reading of this text is indebted to Theodore Jennings, Jr., The Man Jesus Loved: Homoerotic Narratives from the New Testament (

[ii] Fenton Johnson, Geography of the Heart: A Memoir (

[iii] Johnson, p. 234.

1 comment:

Dear Fr. John:

I came across your blog posting and would love to send you a copy of the biogrpahy of Gene Robinson I published a couple of months ago (aklong with a couple other of our books I think you might like...) Might I have your mailing address?

Post a Comment