"An old man said, 'He who lives in obedience to a spiritual father finds more profit in it than one who withdraws to the desert."

"An old man said, 'He who lives in obedience to a spiritual father finds more profit in it than one who withdraws to the desert."- Apophthegmata Patrum

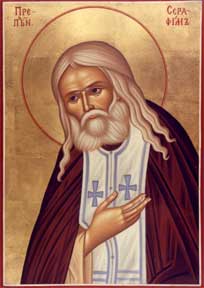

In his book, The Monks of Mount Athos: A Western Monk's Extraordinary Spiritual Journey on Eastern Holy Ground, M. Basil Pennington, OCSO, remarks again and again on the centrality of the Spiritual Father (Elder) in the spirituality of the Orthodox tradition. The Gerontas (Greek) or Staretz (Russian) is a holy man or woman (Gerontessa) to whom one submits in obedience for spiritual direction. According to the Hegumen (Abbott) of Simonos Petras Monastary on Mt. Athos, "The faithful go to church for the Services, Baptism, Eucharist, Penance, but for their spiritual life they go to an Elder." (Pennington, p. 104)

This is not to deny in any way the great value of liturgical and sacramental practice. It is simply a recognition that faith finally must be internalized and experienced; thus, it can only be fully communicated in interpersonal encounter. Although spirituality flows from doctrine (according to Orthodoxy) it must be lived. "Second hand" religion must become "first hand" religion, and for "first hand" religion one must go to a Spiritual Father or Mother.

Pennington's book is full of marvelous insights into the relationship between the Elder and his (or her) spiritual progeny. Such relationships are a much needed antidote to the individualism, narcissism, and solipsism of much of what passes for "spirituality" today, without any touchstone in a living tradition embodied by holy people. I'm grateful for my own Spiritual Father, whose gentleness, wisdom, and love have strengthened my own faith immeasurably.

It isn't easy to find a Spiritual Father or Mother. So much of our culture militates against their development and creates resistance to their acceptance. Our truncated notion of freedom (doing what I want, when I want, how I want) blinds us to the fact that true freedom is exercised on the basis of truth, discernment of reality, and that such discernment requires a trusted and venerable guide or guides. Perhaps the practice of sponsorship in 12-step Recovery programs like Alchoholics Anonymous is an attempt to fill this need.

Among the Orthodox, an Elder is not necessarily an ordained person or the Abbott of the monastary; in fact one's Abbott and one's Elder in the monastary are frequently two different people. It is important in our time, I think, to recover this tradition of the Elder. All of us who exercise pastoral ministry can be edified by the wisdom gained from its observance. As Pennington writes,

"In my contact with the Spiritual Fathers [at Mt. Athos], I am eager to get as much as I can. But in their practice, they are content to give the disciple but a word and let him chew on it for a time and then return for another. The disciple in his reverence considers it a privilege to be able to approach the Gerontas and receive a word. The Fathers realize that growth and insight come from God and they are willing to abide his time. I see that in working with my sons I have been too eager to see them move on, too eager to impart knowledge. For the future I will try to move more at God's pace, be content to give a word, and let it be used by him as he sees fit. Also, I note that the Fathers are slow to give their time to the disciple, not out of any unwillingness to give or lack of openness to the disciple. But they have engendered in them this reverence and contentment with a word. And they realize they can better serve their sons by prayer and sacred reading - growing themselves - than by a lot of talking. I should have reverence for my own time and guard it with due care and not let it be taken headlessly. Yet the Fathers do not hesitate to spend moments in leisure with the brethren, enjoying pleasantries, etc. There is a full humanness about them." (Pennington, p. 50)

Although written from a monastic context, there is much here for lay and ordained "Elders" in a parish context to ponder as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment