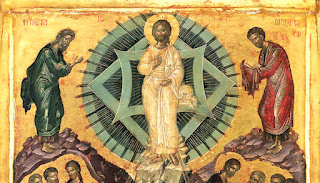

Today we celebrate the Feast of the

Transfiguration of our Lord Jesus Christ. The Transfiguration is attested in

all three Synoptic Gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke, as well

as by the Second Letter of Peter. While the Gospel of John does not include an account of the Transfiguration,

it explicitly underscores the theological significance of the event in an

important dialogue between Jesus and Philip.

Philip said to him,

“Lord, show us the Father, and we will be satisfied.” Jesus said to him, “Have

I been with you all this time, Philip, and you still do not know me? Whoever

has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’? Do you

not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me? The words that I

say to you I do not speak on my own; but the Father who dwells in me does his

works. Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father is in me; but if you

do not, then believe me because of the works themselves. Very truly, I tell

you, the one who believes in me will also do the works that I do and, in fact,

will do greater works than these, because I am going to the Father. (John 14:8-12)

All four Gospels make the same

point: in seeing Jesus, we see God. And in seeing God, we are empowered to become

fully ourselves: human beings created in

God’s image. Through Christ, we become

united with God in the creative, life-giving work of love.

This teaching is at the heart of

Christian faith. It was expressed

beautifully by Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon in the Second Century, when he wrote

that "The glory of God is man fully alive, and the life of man is the

vision of God. If the revelation of God through creation already brings life to

all living beings on the earth, how much more will the manifestation of the

Father by the Word bring life to those who see God" (Against Heresies IV, 20, 7).

This vision of God is made possible through "the Word of God, our

Lord Jesus Christ, Who did, through His transcendent love, become what we are,

that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself." (Against Heresies V, preface)

This is a great mystery, and it is astonishing to realize

that God desires to freely share God’s life and glory with us! God desires so much more for us that we can

ask for or imagine! How patiently God waits for us to wake-up to

our desire for God, to become united with his will for us, which is true

freedom and joy.

In Luke’s account, Jesus brings Peter, James, and John up to

the mountain to pray. The three

disciples struggle to remain awake, but in doing so see the glory of God

revealed there. This is the work of

prayer: the struggle to shake off our

illusions and preoccupations, so that we can attend to God’s desire for us and

our desire for God. Prayer is the work

of seeing God so that we can see ourselves as God sees us. Prayer is waking-up

so that we don’t miss the point of being alive!

Prayer can be a struggle, much as attending to any

relationship can be a struggle. It takes

effort and perseverance, time and attention, for a real relationship with

another human being to unfold, to move beyond our projections and illusions

about each another to that we can really see each other. Genuine friendship is the fruit of such

effort; accepting one another as we really are so that we can grow into the

fullness of who we are meant to be. Real friends love each other, and they

accept each other, warts and all, thereby providing each other the space and

time to let go of those things that prevent them from becoming fully

alive.

St. Theresa of Avila describes prayer in much the same

way. She writes that “prayer in my

opinion is nothing else than an intimate sharing between friends; it means

taking time frequently to be alone with Him who we know loves us. In order that love be true and the friendship

endure, the wills of the friends must be in accord . . . Oh what a good friend

You make, my Lord! How You proceed by

favoring and enduring. You wait for

others to adapt to Your nature, and in the meanwhile you put up with theirs!” (The

Book of Her Life, VIII, 5-6)

Like any good friend, God puts up with us until we can see

ourselves through God’s eyes: as objects of God’s loving desire, invited to

share God’s life and work. Prayer is the experience of God loving us

until we can love ourselves. Then God

loves us some more, until we begin to love others as God loves us. We adapt ourselves to God’s nature and so

become like Jesus.

Good friends also listen to each other, deeply and

patiently. The voice from the cloud

announces to Peter, James and John: “this is my Son, my Chosen, listen to him!”

(Luke 9:35). The vision of God in the

face of Jesus Christ also entails a willingness to listen to his voice, to

internalize his teaching, not simply to venerate him but to follow him, to

become like him. How do we do this?

In Eastern Orthodox tradition, the Feast of the

Transfiguration is a celebration of the chief end of human life: deification or union with God’s will. This is called theosis in the Eastern Church, a process of transformation through catharsis (purification of mind and

body) and theoria (illumination by

the vision of God). Theosis is not our achievement, but

rather God’s gift to us, whereby we become transparent to the energia of God in the power of the Holy

Spirit. The practice of prayer disposes

us to become willing to receive this gift, empowering us for service in God’s

name.

In English, theoria

is translated as “contemplation.” Gerry May defines contemplation “as a

specific psychological state characterized by alert and open qualities of

awareness . . . contemplation consists of a direct, immediate, open-eyed

encounter with life as-it-is.”

Contemplation as a psychological state occurs naturally and can be

taught, learned, and cultivated. May

notes that when practiced over time, the psychological state of contemplation

produces changes in brain function, with quite visible psychophysiological

effects:

1 1.Increased clarity and breadth of awareness: the experienced contemplative develops a

capacity for more panoramic, all-inclusive awareness that includes stimuli that

is normally screened out as distracting or irrelevant. Thus more information is available for

consideration.

22. More direct and incisive responsiveness to

situations. Since a greater range of

perception is available, the experienced contemplative is more present in the

moment and responsive to people and situations.

At the same time, she is increasingly confident in the mind’s natural

intuitive ability, thus spending less time consciously thinking about what to

do. This combination of increased

information and decreased effort makes for more immediate and efficient

reactions.

33. Greater self-knowledge. Mental activities that were previously

unnoticed become visible; the unconscious becomes conscious, increasing

understanding of thoughts, sensations, emotions, and memories. Personal abilities and vulnerabilities are

better understood and accepted. Most

importantly, the insubstantiality of one’s self-image is recognized, making one

less vulnerable to a variety of existential anxieties.

All of this makes for a remarkable increase in personal

power, but at the level of technique, contemplation is morally neutral: it can be cultivated for great good or for

great evil. Contemplation becomes

contemplative prayer only when it is directed toward a conscious desire for God

and knowledge of God’s will. This is

also why, in the Christian tradition, the practice of contemplation is always

done in conjunction with the cultivation of the virtues, especially the

theological virtues of faith, hope, and love.

Here, we move beyond honing neurological responsiveness and

personal power to cultivating a willingness to be open to God’s grace,

embracing the vulnerability of friendship with God of which St. Teresa

speaks. Contemplative prayer is a

willingness to embrace the vulnerability of loving and being loved.

In contemplative prayer, we reach the limit of what training

and effort can achieve, and surrender to the healing and transfiguring power of

God’s love.

We cannot make the vision of

God happen.

We can dispose ourselves to

become willing to receive it, to risk the vulnerability of love.

This willingness is risky.

In prayer, St. Catherine of Genoa heard God say,

“If you know how much I loved you, it would kill you.”

How much love can we bear?

May argues that the only psychological

determinant that correlates with our capacity for love is our willingness to

accept the pain of love and the courage to bear it.

Love can hurt, but it also heals like nothing

else can.

[1]

In the Kontakion

for the Feast of the Transfiguration, our Eastern Orthodox sisters and brothers

sing,

On the Mountain You were Transfigured, O Christ God,

And Your disciples beheld Your glory as far as they could

see it;

So that when they would behold You crucified,

They would understand that Your suffering was voluntary,

And would proclaim to the world,

That You are truly the Radiance of the Father!

In Christ, God willingly risks the vulnerability of love for

the sake of life, for our life and the life of the world. In contemplative prayer, we gamble on that

same risk and surrender to this love. We

become truly ourselves: icons of God’s own love, united with God in the work of

justice, healing and reconciliation. For

this, we were made. Amen.